It’s probable you’ve already replied to a couple of emails today, sent some chat messages and maybe performed a quick internet search. As the day wears on you will doubtless spend even more time browsing online, uploading images, playing music and streaming video.

Each of these activities you perform online comes with a small cost – a few grams of carbon dioxide are emitted due to the energy needed to run your devices and power the wireless networks you access. Less obvious, but perhaps even more energy intensive, are the data centres and vast servers needed to support the internet and store the content we access over it.

Although the energy needed for a single internet search or email is small, approximately 4.1 billion people, or 53.6% of the global population, now use the internet. Those scraps of energy, and the associated greenhouse gases emitted with each online activity, can add up.

The carbon footprint of our gadgets, the internet and the systems supporting them account for about 3.7% of global greenhouse emissions, according to some estimates. It is similar to the amount produced by the airline industry globally, explains Mike Hazas, a researcher at Lancaster University. And these emissions are predicted to double by 2025.

If we were to rather crudely divide the 1.7 billion tonnes (1.6 billion tons) of greenhouse gas emissions estimated to be produced in the manufacture and running of digital technologies between all internet users around the world, it means each of us is responsible for 400g (14oz) of carbon dioxide a year.

Popular music videos such as Despacito can have a large carbon footprint if they are streamed billions of times (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

But things are not that simple – this figure can vary depending where in the world you are. Internet users in some parts of the globe will have a disproportionately large footprint. One study estimated that 10 years ago, the average Australian internet user was responsible for the equivalent of 81kg (179lbs) of carbon dioxide (CO2e) being emitted into the atmosphere. Improvements in energy efficiency, economies of scale and use of renewable energy will doubtless have reduced this, but it is clear that people in developed nations still account for the majority of the internet’s carbon footprint. (CO2e is a unit used to express the carbon footprint of all greenhouse gases together as if they were all emitted as carbon dioxide)

For some, the realisation that their online activity is harming the planet has spurred them into taking action.

“Anything we can do to reduce carbon emissions is important, no matter how small, and that includes how we behave on the internet,” says Philippa Gaut, a teacher from Surrey, UK. She is one of a growing number of eco-conscious consumers trying to reduce their environmental impact online and on their phones. “If everybody made changes, it would have more impact,” she adds

One of the difficulties in working out the carbon footprint of our internet habits is that few people can agree on what they should and should not include. Should it include the emissions that come from manufacturing the computing hardware? And what about those from the staff and buildings of technology companies? Even the figures around the running of data centres are disputed – many run on renewable energy, while some companies buy “carbon off-sets” to clean up their energy use.

While many companies claim to power their data centre’s using renewable energy, in some parts of the world they are still largely powered from the burning of fossil fuels

In the US, data centres are responsible for 2% of the country’s electricity use, while globally they account for just under 200 terawatt Hours (TWh). According to the United Nation’s International Telecommunications Union, however, this figure has flatlined in recent years despite rising internet traffic and workloads. This is largely because of improved energy efficiency and the move to centralise data centres into giant facilities.

But while many companies claim to power their data centre’s using renewable energy, in some parts of the world they are still largely powered from the burning of fossil fuels. And it can be difficult for consumers to choose which data centres they want to use. Many of the major cloud providers, however, have pledged to cut their carbon emissions, so storing photos, documents and running services off their servers where possible is one approach to take.

As an individual, simply upgrading our equipment less often is one way of cutting the carbon footprint of our digital technology. The greenhouse gases emitted while manufacturing and transporting these devices can make up a considerable portion of the lifetime emissions from a piece of electronics. One study at the University of Edinburgh found that extending the time you use a single computer and monitors from four to six years could avoid the equivalent of 190kg of carbon emissions.

Eco-messaging

We can also alter the way we use our gadgets to cut our digital carbon footprints. One of the easiest ways is to switch they way we send messages.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the footprint of an email also varies dramatically, from 0.3g CO2e for a spam email to 4g (0.14oz) CO2e for a regular email and 50g (1.7oz) CO2e for one with a photo or hefty attachment, according to Mike Berners-Lee, a fellow at Lancaster University who researches carbon footprints. These figures, however, were crunched by Berners-Lee 10 years ago. Charlotte Freitag, a carbon footprint expert at Small World Consulting, the company founded by Berners-Lee, says the impact of emailing may have gone up.

“We think the footprint per message might be higher today because of the bigger phones people are using,” she says.

While spam emails can have quite a small carbon footprint, sending images or large attachments can have a much bigger impact (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Based on the older figures, some people have estimated that their own emails will generate 1.6kg (3.5lb) CO2e in a single day. Berners-Lee himself also calculated that a typical business user creates 135kg (298lbs) CO2e from sending emails every year, which is the equivalent of driving 200 miles in a family car.

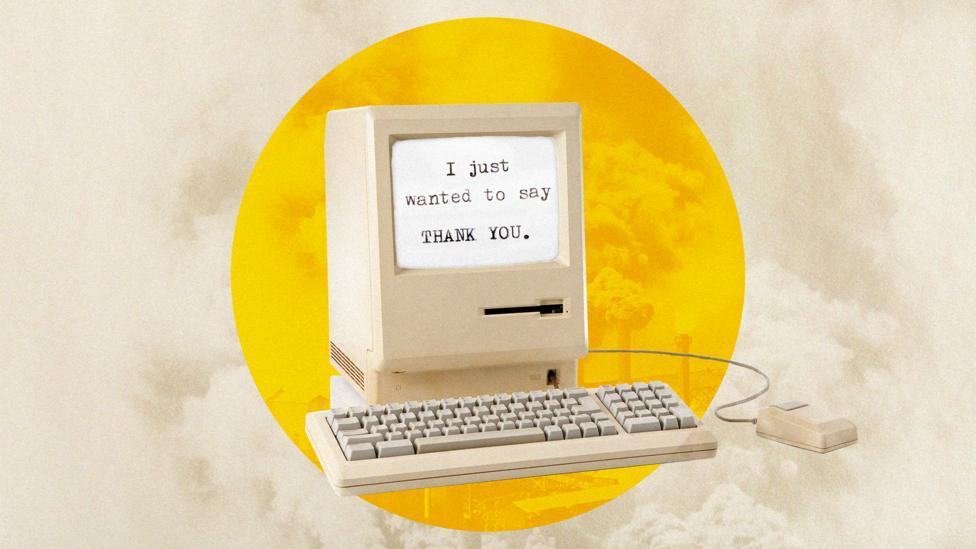

But it should also be easy to cut this down. By simply stopping unnecessary niceties such as “thank you” emails we could collectively save a lot of carbon emissions. If every adult in the UK sent one less “thank you” email, it could save 16,433 tonnes of carbon a year – the equivalent to taking 3,334 diesel cars off the road, according to energy company, OVO.

“While the carbon footprint of an email isn’t huge, it’s a great illustration of the broader principle that cutting the waste out of our lives is good for our wellbeing and good for the environment,” Berners-Lee says.

Swapping email attachments for links to documents and not sending messages to multiple recipients are another easy way to reduce our digital carbon footprints, as well as unsubscribing from mailing lists we no longer read.

“I unsubscribed from automatically generated newsletters, as when I learned about the carbon footprint from emails, I was horrified,” says Gaut. “Now, I’m careful not to send out my email to new websites… it’s made me consider the impact more.”

According to estimates by antispam service Cleanfox, the average user receives 2,850 unwanted emails every year from subscriptions, which are responsible for 28.5kg (63lbs) CO2e.

If every adult in the UK sent one less “thank you” email, it could save 16,433 tonnes of carbon a year – the equivalent to taking 3,334 diesel cars off the road

Choosing to send an SMS text message is the perhaps the most environmentally-friendly alternative as a way of staying in touch because each text generates just 0.014g of CO2e. A tweet is estimated to have a footprint of 0.2g CO2e (although Twitter did not respond to requests to confirm this figure) while sending a message via a private messaging app such as WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger is estimated by Freitag to be only slightly less carbon intensive than sending an email. Again this can depend on what you are sending – gifs, emojis and images have a greater footprint than plain text.

The carbon footprint of making a one-minute mobile phone call is a little higher than sending a text, according to Freitag, but making video calls over the internet is much higher. One study from 2012 estimated that a five-hour meeting held over a video conferencing call between participants in different countries would produce between 4kg (8.8lbs) CO2e and 215kg (474lbs) CO2e.

But it is important to remember where it replaces travel to reach meetings, it can be far better for the environment. The same study found the video conferencing produced just 7% of the emissions of meeting in person. Another study found “the impact of a car ride exceeds the impact of a video conference at less than 20km”.

Clean searching

Internet searching is another tricky area. A decade ago, each internet search had a footprint of 0.2g CO2e, according to figures released by Google. Today, Google uses a mixture of renewable energy and carbon offsetting to reduce the carbon footprint of its operations, while Microsoft, which owns the Bing search engine, has promised to become carbon negative by 2030, and efforts are underway to investigate whether this footprint is now higher or lower.

According to Google’s own figures, however, an average user of its services – someone who performs 25 searches each day, watches 60 minutes of YouTube, has a Gmail account and accesses some of its other services – produces less than 8g (0.28oz) CO2e a day.

Spending less time on niceties such as short, unnecessary “thank you” messages could also reduce the carbon footprint of your email (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Newer search engines, however, are attempting to set themselves apart as greener options from the outset. Ecosia, for example, says it will plant a tree for every 45 searches it performs. This sort of carbon offsetting can help to remove carbon from the atmosphere, but the success of these projects often depends on how long the trees grow for and what happens to them when they are chopped down.

Regardless of the search engine you choose, using the web to find information is more sustainable than browsing in books. In fact, a paperback’s carbon footprint is around 1kg (2.2lbs) CO2e, while a weekend newspaper accounts for between 0.3kg (10oz) and 4.1kg (9lbs) CO2e making reading the news online more environmentally friendly than poring over a paper.

But you could still read a lifetime of paperbacks – 2,300 to be precise – for the same carbon footprint as a flight from London to Hong Kong, so don’t feel too guilty for reading the next best seller. (Read more about how to reduce the impact your flights have on the environment.)

Those who have been tempted by cryptocurrencies might also want to think carefully about the environmental impact of the transactions they conduct. Vast amounts of computing power are needed for the so-called “proof of work” algorithm that is used to validate transactions on Blockchain’s distributed ledger system. One recent study estimated that BitCoin alone is responsible for around 22m tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions every year – greater than all the carbon footprint of the whole of Jordan.

Beating boredom

Watching online videos accounts for the biggest chunk of the world’s internet traffic – 60% – and generates 300m tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, which is roughly 1% of global emissions, according to French think tank, The Shift Project. This is because, as well as the power used by devices, energy is consumed by the servers and networks that distribute the content.

“If you flip on your television to watch Netflix, around half the power goes into powering the TV and half the energy goes into powering Netflix,” says Lancaster University’s Mike Hazas. Some experts, however, insist that the energy needed to store and stream videos is less than more intensive computational activities performed by data centres.

Pornography accounts for a third of video streaming traffic, generating as much carbon dioxide as Belgium in a year

Some of the climate pollution that comes from internet use also comes from some rather dirty browsing. Pornography accounts for a third of video streaming traffic, generating as much carbon dioxide as Belgium in a year.

On-demand video services such as Amazon Prime and Netflix account for another third while the final third of the video streaming carbon footprint includes watching YouTube and clips on social media. Netflix says its total global energy consumption reached 451,000 megawatt hours per year, which is enough to power 37,000 homes, but insists it purchases renewable energy certificates and carbon offsets to compensate for any energy that comes from fossil fuel sources.

Streaming and downloading music also has an impact. Rabih Bashroush, a researcher at the University of East London and lead scientist at the European Commission-funded Eureca project, calculated that five billion plays clocked up by just one music video – the hit 2017 song Despacito – consumed as much electricity as Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Somalia, Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic put together in a single year. “The total emissions for streaming that song could be over 250,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide,” he says.

However, Hazas points out that some YouTube views are unintentional. A study led by his colleague Kelly Widdicks analysed streaming habits and found that some viewers use YouTube as background noise, and sometimes even fall asleep, generating carbon for no gain. Cutting back on these uses or stopping video from playing unintentionally on an open browser when you are not watching, could help keep your carbon footprint down.

Using online videos to drift off to sleep or as background noise places unnecessary demand on data centres and harms the climate (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

Fiddling with autoplay settings and switching from high definition to a lower resolution when it’s not necessary can also make a difference. Hazas says the most efficient way to see your favourite programme is by waiting for it to be on terrestrial TV, or choosing to stream it over wi-fi rather than on a mobile network can also make a difference.

“Using a phone over a mobile network is at least twice as energy intensive than using it over wi-fi, so if you can wait until you get home to watch YouTube that’s best,” he adds. And, one of the most enjoyable ways to be more environmentally friendly is to watch films and TV together.

“On the whole, audio is less problematic,” says Hazas, as streaming audio is less energy and carbon intensive than streaming images. But researchers at the University of Oslo found that environmental impact of listening to music has never been higher, with a footprint of 200,000-350,000 tonnes of CO2e in the US alone for downloading tracks onto MP3 players. It’s thought emissions for streaming services may be even higher.

However, the number of times you listen to a piece of music can make a difference. Buying a physical CD or record can be better if you listen to the same album repeatedly, but if you only listen to a piece of music less than 27 times over your lifetime, then streaming can be better. (Read more about the carbon footprint of streaming music.)

Similarly, the environmental cost of downloading video games is thought to be higher than producing and distributing Blu-Ray disks from shops. The first attempt to map the energy use of gaming in the US found it produces 24 megatonnes of carbon dioxide a year. Researchers behind the study at the University of California found US gamers use 2.4% of their household electricity – 32 terawatt hours of energy every year – which is more than freezers or washing machines. They also showed that streaming games uses more energy, so gaming carbon emissions may worsen as more people adopt games where the computational work is being done remotely rather than on individual consoles, such as with devices like Google’s Stadia.

Reading news or books online produces less greenhouse gases than the same content on paper (Credit: Getty Images/Javier Hirschfeld)

But Hazas is more optimistic. “The carbon footprint of playing multiplayer games like Fortnite isn’t too bad,” he says. “They are designed to be responsive so they don’t require too much data traffic. For example, you get a position of a character on a map, or the fact someone’s shooting, but it doesn’t take too much data to communicate that.”

However, updating games is more carbon intensive. “Flagship games like Fortnite or Call of Duty require lots of updates so you’re looking at gigabytes every couple of weeks for downloads, which add new features.”

For those who enjoy flicking through their social media, there is some good news. It is arguably the least carbon intensive form of digital entertainment. According to Facebook’s sustainability report, a user’s annual carbon footprint is 299g CO2e, which is less than boiling the water for a pot of tea. But if you consider the platform has more than one billion users, that’s a lot of pots of tea.

It’s possible to save carbon by disabling some features for social media and other apps.

“We’ve found that app updates and automatic cloud backups are about 10% of traffic from mobile phones,” says Hazas. “So, switching off unnecessary cloud backups and switching off automatic downloads for app updates are good things to do.”

But while changes in our personal online behaviour will only take us so far, there also needs to be change within the industry to ensure that carbon emissions can be reduced, says Elizabeth Jardim, a senior corporate campaigner at environmental campaign group Greenpeace. The IT industry’s greenhouse gas emissions are predicted to reach 14% of global emissions by 2040 but at the same time the UN’s International Telecommunication’s Union has set the industry the target of reducing its emissions by 45% over the next decade.

“It’s more important to make sure the companies building the internet are switching to renewable and phasing out fossil fuels,” says Jardim. “That’s when searching will be more guilt free.”

—

Smart Guide to Climate Change

For most BBC Future readers, the question of whether climate change is happening is no longer something that needs to be asked. Instead, there is now growing concern about what each of us as individuals can do about it. This new series, our “Smart Guide to Climate Change”, uses scientific research and data to break down the most effective strategies each of us can take to shrink our carbon footprint.

[“source=bbc”]