On Wednesday, juniors at 92 New York City high schools will pick up their pencils, open their test booklets and take the SAT, with no fee and during regular school hours. It is the first step in a plan to give the test next year in all 438 city high schools, which the de Blasio administration hopes will help make college more accessible for thousands of students.

Participation in college admissions testing has lagged in New York: Only 56 percent of the class of 2015 took the SAT exam at least once. Many have praised the effort to make the exam a baseline expectation for high schoolers. But the initiative also raises difficult questions about whether, without significant preparation, low-income students will do well enough on the SAT to get into colleges where they are likely to succeed.

“The predictors are, if you come from a high-income family or a family that graduated from college, the data is there — their kids are going to do much better on the SATs,” said David O’Hara, the principal of Leaders High School in Gravesend, Brooklyn. He said 90 percent of his students, if admitted, would be the first in their family to attend college. Last year, all his students took the SAT, and their average score was 1212 out of 2400, less than the city average. (This year the test is moving back to a 1600-point scale.)

Mr. O’Hara said he was glad that the Department of Education was setting an expectation that students should apply to college. But he hoped that the city would give schools more money to help prepare students. His school offers yearlong Saturday SAT preparation sessions to 20 juniors, through a partnership with the volunteer organization New York Cares. But there are not enough resources for all 70 students in his junior class, he said.

Low SAT scores have “kept a lot of our very successful students out of some really good colleges,” he said.

The Education Department said that this year it had offered training for teachers at the 92 schools on the content of the new SAT and that in future years it might provide more test preparation resources. The College Board, which administers the SAT, also offers students free access to online preparation materials and practice tests from Khan Academy, a nonprofit organization that provides free educational videos.

The city already offers the Preliminary SAT exams free in school to sophomores and juniors, and students who took that exam in October received a personalized Khan Academy account along with their scores. Neither the College Board nor the city could say how many students in the city had used their accounts. The College Board said that 900,000 students had done so nationally.

Phil Weinberg, the deputy chancellor for teaching and learning at the department, said the goal of offering the SAT to all students was to change the culture and expectations in high schools, rather than to achieve certain scores.

“We want all of our students to know that this part of the process of getting into a postsecondary option is something that we’re going to help them do and that it’s going to be a normal part of their lives,” Mr. Weinberg said.

“We believe that the awareness that we’re creating in the city will help test scores go up, as well,” he said, “but this is not going to be magic.”

Scores on the SAT closely track family income and education and, as in many educational measures, there are stark racial disparities. In 2015, for instance, students whose families made over $200,000 scored more than 100 points higher on both the reading and the math portions of the test than students whose families made $20,000 to $40,000. Among New York City public school students who took the test in 2015, white students scored 98 points higher than black students on the reading portion and 118 points higher on the math portion.

Many middle-class and wealthy families spend a significant amount of money on tutoring or classes to prepare their children for the SAT. The College Board said that 58 percent of the students who took the previous version of the SAT paid for test preparation.

David Coleman, the president of the College Board, said that while simply offering the test during the school day could have a modest effect on scores, the College Board was really looking to other efforts — such as changes to the SAT this year that are intended to make it more closely reflect what students learn in school, as well as the new free preparation materials — to try to narrow the achievement gap.

“We’re really looking at this opportunity of all kids taking it to try to do other things that are helpful,” he said.

At the Business of Sports School last year, the principal, Joshua Solomon, brought in CollegeSpring, a nonprofit that provides test preparation in low-income schools. The group trains a school’s teachers in a curriculum that combines reading and math remediation with SAT practice. It also sends current college students — mostly minorities, and many of them first-generation college attendees — into schools once a week to do small group tutoring. The idea is that the college students will not only do test preparation but also serve as role models.

The test preparation itself is “a little like taking your medicine,” and students do not enjoy it very much, Mr. Solomon said. “So having the college-age mentors come in and really talk about how important it is and talk about college in general is significant.”

The school pays $250 per student for the program, coming from its Title I grant. With juniors spending two to three periods a week doing test preparation with either the school’s teachers or the mentors, it is a significant investment of time.

Shazz Davis, who is part of the test prep program at Leaders High School, said that she decided to apply to the program after being disappointed in her Preliminary SAT scores and worrying that low scores could prevent her from being accepted to her “dream college,” which is Barnard.

“Looking at my performance over all, I have the extracurriculars and the leadership” and the grades, Ms. Davis said. “It’s just my SAT scores, and I know I need to improve on that.”

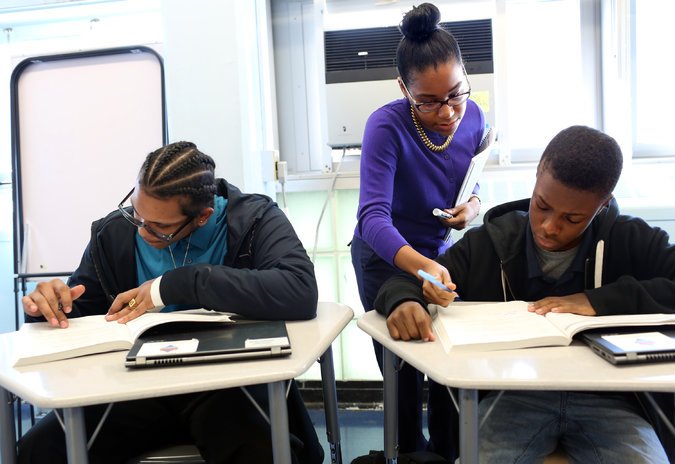

On Saturday morning, she sat in a classroom along with three other female students while Saakshi Gupta, a financial consultant, reviewed the properties of triangles. After the brief lesson, the students tried two practice problems that involved several steps.

“The SAT tries to trick you,” Ms. Gupta warned when Ms. Davis made a wrong assumption about the triangle.

Ms. Davis also struggled with the wording of the problem, which asked students to find the value of an angle, defined as q, in terms of another variable, z.

“I just don’t understand,” Ms. Davis said, sounding frustrated. “If this is the real SAT, how would you find what they’re asking for?”