The United Nations Human Rights Council is taking aim at countries that block access to the Internet as a means to supress free expression.

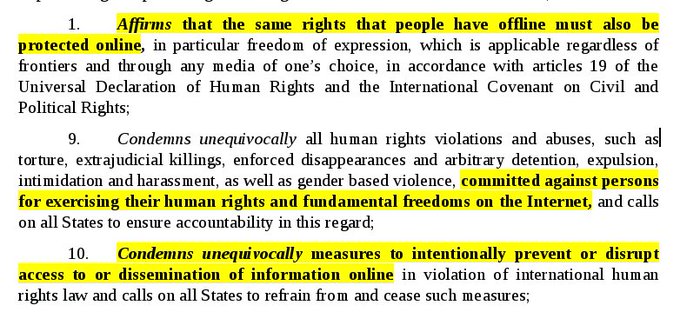

The resolution passed by the 47-member council last week “condemns unequivocally measures to intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online in violation of international human rights law and calls on all states to refrain from and cease such measures.”

Russia, China, and Saudi Arabia were among a handful of authoritarian regimes that asked the UN to strike that passage from the digital rights decree. South Africa and India also called for its removal.

The non-binding resolution also asks nations to harness the power of the Internet to empower women and persons with disabilities, as well as promote literacy and achieve sustainability goals.

Internet blackouts are well-documented across China and the Middle East. The Turkish government recently clamped down on news outlets, as well as Facebook and Twitter, after last month’s suicide attack on Istanbul’s Atatürk Airport that left 36 dead and another 147 wounded. The government-backed action by Turkish Internet service providers was caught by watchdog group Turkey Blocks.

Digital rights group Access Now counted 15 Internet shutdowns in 2015 and says there have been at least 20 so far in 2016.

“Shutdowns harm everyone and allow human rights crackdowns to happen in the dark, with impunity. Citizens can’t participate fully in democratic discourse during elections. The Human Rights Council’s principled stance is a crucial step in telling the world that shutdowns need to stop,” said Access Now Senior Global Advocacy Manager Deji Olukotun in a statement.

The U.S.-based non-governmental organization Freedom House says governments are upping the pressure on Internet service providers and social media sites to block, filter, and remove content.

For example, transparency reports published by Twitter show requests from courts and government agencies have skyrocketed from six per year to over 1,000 in the three years since the micro-blogging site started releasing data.

Freedom House estimates that 34 per cent of the global population lives in countries that heavily restrict Internet access or content, and another 23 percent live in countries with partially restricted access.

The UN resolution, which is not legally enforceable, builds on its previous statements on digital rights and reaffirms its stance that the “same rights people have offline must also be protected online.” This is the organization’s third online rights resolution since 2012, but the first that specifically targets nations that deny access to citizens.

A number of countries, including Canada, have signalled a need to combat the efforts of political regimes bent on controlling free expression online. Ottawa pledged $9 million last year for a project aimed at helping citizens circumvent government imposed restrictions in repressive environments.

U.S President Barack Obama has said that access to high speed broadband Internet is “not a luxury, it’s a necessity.”

Edward Snowden, the former CIA employee who copied and leaked classified information from the U.S. National Security Agency to several media organizations, called the UN’s dedication to the issue “good news” on Twitter Friday.

While the resolution lacks the legal authority to impose changes within countries that choose to censor what is a said and seen online, the move is being heralded as a critical first step in shifting the conversation about such actions into the mainstream.

“This resolution marks a major milestone in the fight against internet shutdowns. The international community has listened to the voices of civil society — many of whom have suffered under shutdowns themselves — and laudably pushed back on this pernicious practice,” said Olukotun.