One of the founding fathers of the internet, Robert Taylor, has died.

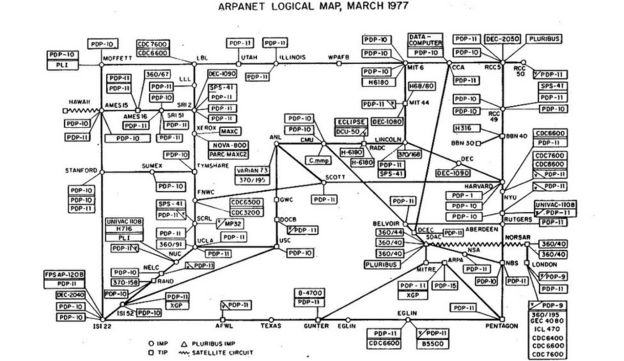

While working at the Pentagon in the 1960s, he instigated the creation of Arpanet – a computer network that initially linked together four US research centres, and later evolved into the internet.

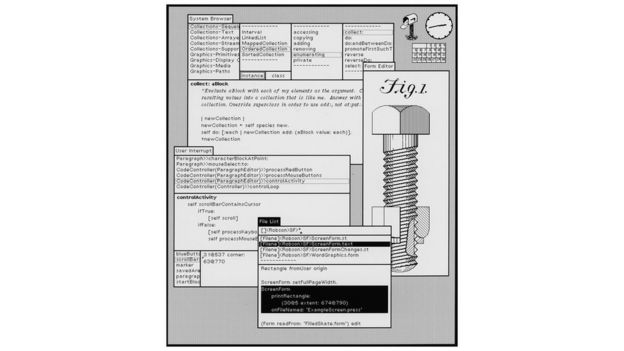

At Xerox, he later oversaw the first computer with desktop-inspired icons and a word processor that formed the basis of Microsoft Word.

Mr Taylor died at home aged 85.

His family told the Los Angeles Times that he had suffered from Parkinson’s disease among other ailments.

Image copyrightXEROX

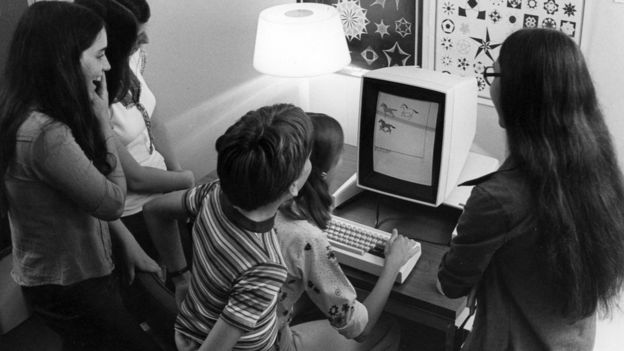

Image copyrightXEROXMr Taylor studied psychology at university, but worked as an engineer at several aircraft companies and Nasa before joining the US Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Project Agency (Arpa) in 1965.

At the time, Arpa funded most of the country’s computer systems research.

In his role as the director of the organisation’s Information Processing Techniques Office, Mr Taylor wanted to address the fact different institutions were duplicating research on the limited number of computer mainframes available.

In particular, he wanted to make “timesharing” more efficient – the simultaneous use of each computer by multiple scientists using different terminals, who could share files and send messages to each other.

Mr Taylor was frustrated that the Pentagon could only communicate with three research institutions, whose timeshared computers it helped fund, by using three incompatible systems.

So, he proposed a scheme to connect all of Arpa’s sponsored bases together via a single network.

“I just decided that we were going to build a network that would connect these interactive communities into a larger community in such a way that a user of one community could connect to a distant community as though that user were on his local system,” he later recalled in an interview with the Charles Babbage Institute.

“Most of the people I talked to were not initially enamoured with the idea. I think some of the people saw it initially as an opportunity for someone else to come in and use their [computing cycles].”

Nevertheless, he was given $1m (£796,000) to pursue the project.

And in 1968, a year before Arpanet was established, he co-authored a prescient paper with a colleague.

“In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face to face,” it predicted.

“The programmed digital computer… can change the nature and value of communication even more profoundly than did the printing press and the picture tube, for, as we shall show, a well-programmed computer can provide direct access both to informational resources and to the processes for making use of the resources.”

Sugar supplies

Mr Taylor’s time at Arpa was also spent trying to see whether his country could make use of computer technology to solve logistics problems during the Vietnam war.

The White House had complained that it was getting conflicting reports about the number of enemies killed, bullets available and other details.

“The Army had one reporting system; the Navy had another; the Marine Corp had another,” Mr Taylor later recalled.

“It was clear that not all of these reports could be true.

“I think one specific example was that if the amount of sugar reported captured were true we would have cornered two-thirds of the world’s sugar supply, or something like that. It was ridiculous.”

His efforts led to a uniform method of data collection and the use of a computer centre at an air force base to collate it.

“After that the White House got a single report rather than several,” Mr Taylor said.

“That pleased them; whether the data was any more correct or not, I don’t know, but at least it was more consistent.”

Apple and Microsoft

Once Arpanet was up and running in 1969, Mr Taylor left the Pentagon and the following year he founded the Computer Science Laboratory of the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox Parc).

Image copyrightXEROX

Image copyrightXEROXThere his team built Alto – a personal computer that claims several firsts. It was networked, controlled by a ball-driven mouse and used a graphical user interface (Gui).

Steve Jobs and others from Apple were given an early look, and it went on to inspire them to create the Apple Lisa and later the Apple Mac.

Its software included Bravo – a what-you-see-is-what-you-get word processor. Its primary developer, Charles Simonyi, later joined Microsoft where he created Word.

Despite their achievements, Mr Taylor became frustrated with Xerox’s failure to capitalise on his team’s work and quit in 1983.

“Xerox continued to ignore our work,” he told an interviewer in 2000.

“I got fed up and left, and about 15 people came and joined me at DEC [Digital Equipment Corporation].”

There he helped create AltaVista, an early internet search engine, and a computer language that later evolved into Java.

Mr Taylor continued to dream of new technologies – predicting that the public would one day wear a device that would record everything they saw or heard.

Image copyrightALTAVISTA

Image copyrightALTAVISTABut he also reflected that his greatest legacy – the internet – had taken longer to catch on than anticipated.

“My timing was awful,” he conceded, adding “I didn’t anticipate [its use for] pornography and crime.”