Along with the American Clean Power Association and the American Council on Renewable Energy, Advanced Energy United requested a rehearing of the United States earlier this month. According to DOE’s Resource Adequacy Report, which was released on July 7, 2025, DOE “missed the opportunity to present all the viable types of energy needed to address reliability and keep energy affordable.” We took this step because, if DOE’s findings were not challenged, they could shape grid policy in a way that forces consumers to pay more for old methods, keeps existing power plants from closing, and ignores proven, cutting-edge energy-based solutions. Background:

What Motivated DOE to Issue a Report?

Following Executive Order (EO) 14262 (Strengthening the Reliability and Security of the United States Electric Grid), DOE issued a release directing it to develop a procedure to expedite orders under Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act (FPA) and evaluate the “reliability and security” of the United States energy grid during an “unprecedented surge in electric demand” caused by the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and data centers. The purpose of Section 202(c) is to direct the temporary connection, generation, delivery, or transmission of electricity in response to an identified emergency—such as a sudden increase in demand or decrease in supply.

DOE, on the other hand, was instructed to report on the potential shortages of future resources, identify the dangers posed by increased demand and the retirement of generators, and then make use of these findings to stop existing resources from leaving the grid in regions that were at risk. Virtual power plants, faster interconnection, new resource development, and load management were not mentioned in the EO.

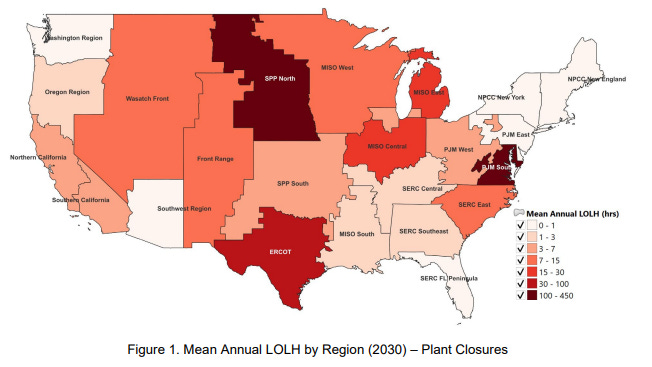

The DOE’s analysis was intended to be a protocol for pursuing a preferred solution to addressing resource adequacy needs, and it should not be interpreted as such. DOE blames AI-driven demand growth, overreliance on renewable generation, and retirement of existing generation that outpaces firm, dispatchable additions for significant blackout risks in 2030 in this protocol. Deficits in the Report Our rehearing request details several critical flaws with these findings and with the process leading up to the protocol’s release.

First, although DOE labeled this as a “report,” it qualifies as a rule under the Administrative Procedure Act, making it subject to rehearing challenges. The protocol was issued without a notice-and-comment period, failed to identify any qualifying “emergency” to justify action under 202(c), exceeded statutory authority by effectively claiming regulatory control over resource adequacy (which is reserved for the states and other federal regulators), and disregarded the Information Quality Act’s requirements for peer review, replicability, public input, and the use of the best available data. These are examples of procedural flaws. Substantively, the protocol’s findings are also flawed as a result of DOE’s unrealistic and internally inconsistent assumptions. To put it succinctly, the protocol selects edge-case inputs rather than performing scenario-based analysis, which results in an unrealistic worst-case projection of future risk. Specifically, the protocol:

assumes extremely low additions of resources. Despite nearly 2,000 GW of resources waiting in interconnection queues, the protocol assumes only 209 GW of new resource entry between now and 2030. This is due to DOE’s open admission that it assumes virtually no resource entry after 2026, which is a particularly unrealistic assumption in light of the high load growth numbers that the report also assumes. DOE only uses very late-stage projects. There are neither alternative cases nor sensitivities that take into account higher resource entry. includes retirements with high resources. In comparison to the most recent assessments conducted by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) and the United States, the single retirement scenario included in the protocol assumes roughly twice as many resource retirements by 2030. Administration of Energy Information. erroneously portrays load growth. Although the protocol assumes high load growth from AI and data centers, among other drivers, the protocol only includes one load growth scenario that does not account for uncertainty and overlooks opportunities to manage this growth. Contrary to the report’s overall conclusion, the protocol also acknowledges that resource planners would not permit load growth to compromise reliability.

Economic development opportunity costs are more appropriate terms for demand growth that exceeds supply than reliability risks. Overlooks state and RTO planning tools. When shortfalls occur, planning tools and market signals are used by states and RTOs, the entities tasked with ensuring resource adequacy. These measures are completely ignored by the report. Understates winter reliability risks for thermal generation. DOE relies on historical datasets that include extreme weather events that exposed the vulnerabilities of the thermal resource fleet—yet reaches the unsupported conclusion that more of these resources would prevent blackouts.

Disregards the resource adequacy benefits of interregional transmission. Despite relying on the data and methodology of a recent NERC report that identified 35 GW of “prudent” interregional transfer capability needs, the report does not take into account the significant resource adequacy benefits that connections between grid regions can provide.

What DOE’s Approach Really Means

A report that assumes significant load growth, high resource exit, and low resource entry will undoubtedly produce a “red alert” result. However, the purpose of the report is to prevent the retirement of power plants, not as a thought experiment to determine the worst-case scenario. We have already seen DOE take action under Section 202(c) to forestall upcoming plant retirements (e.g., Campbell in MI and Eddystone in PA). This approach risks propping up plants where closure may be justified, and risks undermining more affordable, durable solutions to the larger, long-term demand crisis.

As a case in point, a recent study by Grid Strategies titled “The Cost of Federal Mandates to Retain Fossil-Burning Power Plants” found that keeping old, inefficient fossil fuel plants running beyond their useful life would cost consumers more than $3 billion per year. This analysis looked at plants that are scheduled to retire by 2028 and others that may announce retirements in an effort to receive ratepayer subsidies to stay open, given the DOE’s willingness to hand out subsidies to fossil plants, whether they are needed for reliability or not. As a result of their inability to compete with more recent, more productive models, these plants are set to retire. Their retirements were typically approved by RTOs/ISOs, state regulators, or both. According to Grid Strategies’ study, ratepayer costs could reach nearly $6 billion annually if additional fossil fuel power plants move up their retirement dates in response to this DOE protocol. Solutions for A Reliable, Affordable Grid

In the end, DOE’s resource adequacy report does not provide the kind of measured assessment of the grid’s future that should be used to make decisions about resource planning. It also ignores the solutions that are available to deal with the problems caused by rapid load growth. Properly crediting renewable resources for their contribution to grid reliability, and faster interconnection of all resources to the grid, are among the solutions DOE could easily encourage, instead of subsidizing old, inefficient plants that cost ratepayers and provide few benefits.

DOE’s protocol could have a significant impact on resource outcomes given the explicit intention to rely on this report to prevent the retirement of power plants. However, the protocol does not take into account the cost implications, consults appropriately with states and grid operators, or evaluates alternatives.