/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/54086381/Ground_view_near_hyperloop02_WEB.0.jpg)

The year is 2030. Former president Donald Trump’s border wall, once considered a political inevitability, was never built. Instead, its billions of dollars of funding were poured into something the world had never seen: a strip of shared territory spanning the border between the United States and Mexico. Otra Nation, as the state is called, is a high-tech ecotopia, powered by vast solar farms and connected with a hyperloop transportation system. Biometric checks identify citizens and visitors, and relaxed trade rules have turned Otra Nation into a booming economic hub. Environmental conservation policies have maximized potable water and ameliorated a new Dust Bowl to the north. This is the future envisioned by the Made Collective, a group of architects, urban planners, and others who are proposing what they call a “shared co-nation” as a new kind of state.

Many people have imagined their own alternatives to Trump’s planned border wall, from the plausible — like a bi-national irrigation initiative — to the absurd — like an “inflatoborder”made of plastic bubbles. Made’s members insist that they’re serious about Otra Nation, though, and that they’ve got the skills to make it work. That’s almost certainly not true — but it’s also beside the point. At a time when policy proposals should be taken “seriously but not literally,” and facts are up for grabs, Otra Nation turns the slippery Trump playbook around to offer a counter-fantasy. In the words of collective member Marina Muñoz, “We can really make the complete American continent great again.”

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8280889/OtraNation_map02_4000.jpg)

If nothing else, the Made Collective’s members — who say they’ve delivered their Otra Nation proposal to the US and Mexican governments — are ambitious. The proposal calls for an agreement that would turn the border into an unincorporated territory for both nations, with an independent local government and non-voting representatives in the US and Mexican legislatures. The new territory would stretch for 2,000 kilometers, covering 20 kilometers on each side of the border. (That would bring Tijuana, El Paso, and San Diego, among other cities, into Otra Nation.) Residents of the co-nation would retain their previous citizenship, but they would be granted a new ID microchip and could rely on Otra Nation’s independent health care and education systems.

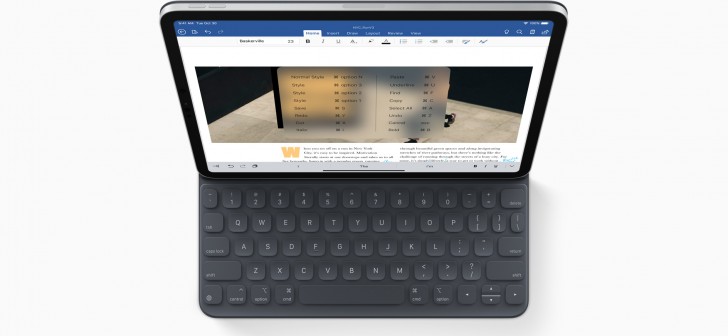

Once established, Otra Nation would supposedly produce enough energy to power itself and neighboring areas, thanks to 90,000 square kilometers of solar panels that would be installed across the deserts. Its new government would dismantle the central US-Mexico border in favor of biometric checkpoints on each side of Otra Nation, preserving and restoring watersheds and local ecosystems. It would build an intercity hyperloop network across the country, starting in the sister cities of San Diego and Tijuana. A set of “sharing principles” would encourage the growth of companies like Airbnb and Lyft, but prohibit ones that “look to minimize human employment with autonomous vehicles and drone technologies” — in other words, no Uber.

Parts of the proposal, like the hyperloop, feel like science fiction worldbuilding or Silicon Valley fanfic, and the whole thing is written with the casual confidence of someone proposing a landscaping project, not a massive political shift built on technology that doesn’t even exist. It’s not clear how serious its authors are about their proposal, even when you speak to them. On Skype, members admit there’s a “very, very slim” chance the US and Mexican governments will be amenable to Otra Nation. But they say they’ve formally applied for a US government contract, and they’re hoping to put the issue up for a popular referendum, which they compare to the 2016 Brexit vote. “We should at least have the opportunity for both nations to vote on a solution,” says architect and humanitarian Cameron Sinclair.

Sinclair, who co-founded the nonprofit Architecture for Humanity and won a TED Prize in 2006, was the most high-profile Made Collective member I spoke to. Team members decline to put their names or faces on the website; their group photo shows human figures with animal heads pasted above their shoulders. Sinclair and others say that the group remains quasi-anonymous in order to keep the focus on Otra Nation, rather than the people behind it. In addition to generalist architects and designers, Made supposedly includes members with close ties to past US and Mexican government administrations. One person also claims to be working on an undisclosed hyperloop-related project.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8280897/Aerial_Near_ElPaso01_04_WEB.jpg)

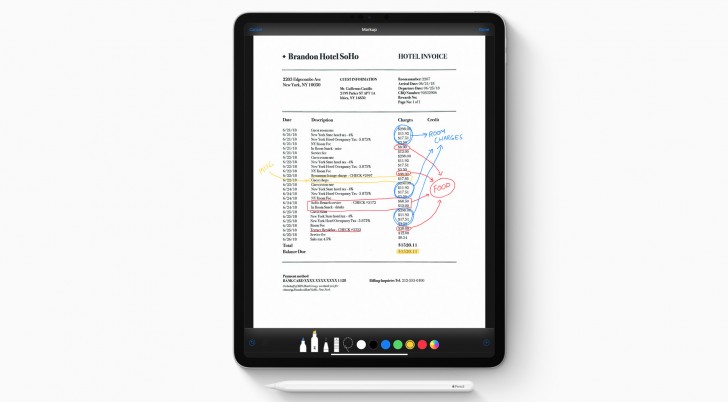

When I ask for a best-case scenario for founding Otra Nation, Sinclair outlines a complex but surprisingly compact roadmap. By 2018, the US and Mexico would sign a bilateral agreement to form the zone, and the estimated 40 million future members of Otra Nation would have their own vote, guaranteeing their consent. Meanwhile, the Made Collective would secure funding in the form of either government contracts or multi-billion-dollar private investments. The group would begin working with companies to lay hyperloop and solar power infrastructure, while also creating the biometric ID system for citizens. “I would say by 2022 we would be underway,” he says. “if everything went well, including getting the vote from the people that would now become residents of Otra Nation, I would say [it could open] by the mid-2020s.”

In reality, getting past the first step would be extraordinary. The US has unincorporated territories like Puerto Rico, and there are plenty of disputed areas, micronations, and special economic zones. But University of Colorado professor John O’Loughlin, who studies quasi-recognized de facto states, called Otra Nation a “pie-in-the-sky” idea. “I have never heard of such an arrangement,” he told The Verge. University of York professor Nina Caspersen, who also works on de facto states, was intrigued but skeptical. “This sounds like a fascinating idea, but without much precedent,” said Caspersen, who suggested Andorra — a small nation headed by co-princes from its neighbors France and Spain — as a possible precedent. But even if the US and Mexico agreed to share the border, many questions would remain. “Could it work in practice? Hard to say,” said Caspersen. The countries could end up in disputes over defense, border security, or anything else Otra Nation’s government couldn’t manage alone.

Basic questions about Otra Nation remain unsettled. The team describes a sophisticated biometric ID program at the borders of Otra Nation, but there’s also a heavy dose of utopianism — as architect and collective member Tegan Bukowski puts it, people will respect borders because the borders are no longer oppressive. “I think what we’re proposing is a trust-based enforcement, rather than the idea that it’s a security based enforcement,” says Sinclair. It’s not even clear how the nation will keep itself running after the initial investment period. “I don’t think we’ve actually figured out the tax system yet,” Sinclair admits.

Whether Otra Nation is a long-shot proposal or a pointedly political art project, Made Collective is effectively mirroring the administration’s approach to the wall: an unprecedented civil engineering initiative that exists more vividly in the realm of imagination than policy. As we talk, members argue that their plan would take less time and money than the border wall, even pledging the leftover funds to arts and education agencies. Otra Nation’s proposal can be vague and sweeping, but so is Trump’s plan for a massive, constantly changing, possibly invisible, and supposedly Mexico-funded barrier. When real governmental goals are blatant fantasy, why not present your own wildest hopes as a viable alternative?

[Source:- The Verge]